|

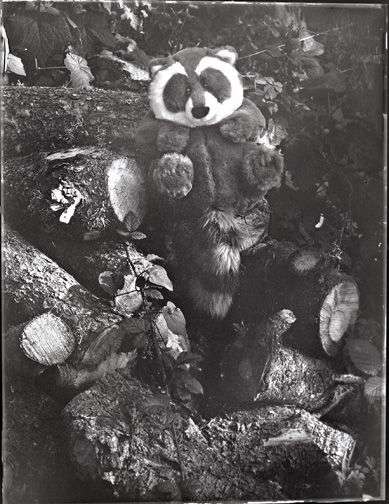

Since the beginnings of photography, rendition of color and brightnesses have been

conventionalized by the limitations of the negative material. In

the early days, with the color-blind plates sensitive only to blue

light, we became accustomed to white skies, dark lips, and very dark

foliage. Later, with orthochromatic emulsions, responding to all

parts of the spectrum except deep orange and red, foliage could be

rendered more faithfully, but skies were still light and blank, lips

still dark, and the rendition of clouds in landscape was considered a

great feat. But with the appearance of the panchromatic emulsions,

responding to the entire visible spectrum, we grew accustomed to dark

skies (exaggerated by the use of filters), light lips, and many other

representations that have become as "conventional" as those of earlier times.

The modern photographer, however, has such a wide choice of negative

materials, together with filters to modify their effects, that he need

be bound by no conventions of expression. After learning

— through experience plus logical experimentation —

the differences between emulsion types, and the effects of various filters

on tonal values and contrast, he has available a stimulating gamut of

interpretive possibilities.'

Ansel Adams, The Negative, 1948, pp 4-5.

|