Overview'Imperfections' |

|

The Perfection Delusion

I've come to accept, and maybe even celebrate, that emulsion (at least ‘I♥’) comes in three varieties: Crap, Fairydust, and Full Monty. It's been awhile since I made Crap. That was mostly a question of getting the surfactant right and taking temperature control seriously. My goal has been reliable Full Monty. That's what I want when I print foggy landscapes or other high key images. No peppering at all. Fairydust is the stuff that has microscopic peppering (literally visible only through a microscope) with the very rare visible black grain. I don't consider it a big issue. I just keep out the 'busy' negatives or the new negatives I'm testing for Fairydust and save the foggy images for Full Monty. What's interesting is that a Fairydust batch of emulsion can be particularly pretty. The highlights have a life of their own and the blacks are deep and lustrous, but there's no mistaking the microscopic peppering (silver halide grain aggregates that are black upon development even without being exposed to light). It turns out that "perfection" may not even be the right goal. Which leads to a thought: A certain amount of control over any process is a satisfying - and necessary — thing, but I wonder if a need for too much control, with the goal of the handmade product indistinguishable from a commercial one, is exactly the wrong approach to take. It changes the goal line from creative control to perfection and is strangely at odds with the attitude that digital, for example, is "too perfect". The concept that the only acceptable photograph is a flawless photograph is a brand new one. It came to us with digital and Photoshop and the 'delete' key. The photographers we look back to for inspiration had a different view. |

Through Another Lens - My Years with Edward Weston, by Charis Wilson and Wendy Mader, North Point Press, 1998. |

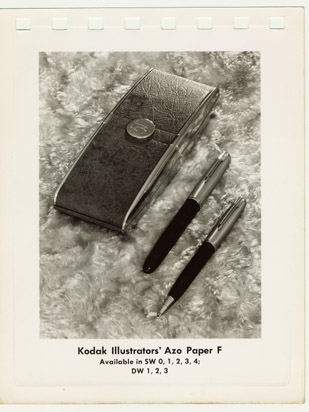

| And even the iconic commercial products had character. I got curious enough to look at old Kodak paper samples through a microscope. I don't know for sure the date of the paper sample book, but from the look of the models, I'd guess mid-to-late 1940's. From the left: 1) a 100% scan of Azo paper, glossy, 2) a half-inch square section of the Azo, enlarged 1000%, and 3) a half-inch square section of 'Secret Garden' (the full print is in Section V. below) enlarged 1000%. The microscopic peppering is visible at extreme magnification. |

|

|

|

|

Spotting

'Pepper' spots can be removed with a fine, sharp needle. ( I further sharpened my spotting needle on a whetstone.) It's very much like removing a tiny sliver from a child's finger. Magnification helps. The result is essentially invisible on any paper except baryta. White spots are treated the same way as on commercial paper (dyes and a tiny brush). |

|

Coming:

More traditional retouching procedures

|

|

Replace This Text in js

Replace This Text in js

|

Copyright © The Light Farm |